Code Reviews: Before You Even Run The Code

Over time I’ve developed some particular processes that I find helpful when reviewing code. In particular, I often surprise people at how much review I do before I run the code. Sometimes I grab the branch so that I can use my local diff tools, but I don’t actually execute code until I’ve established some basic facts. This post is a little insight into what’s happening in this not-running-the-code-yet zone.

Do You Know What This Change Does?

This problem comes up more in open source than it does at work (but not exclusively), I get what looks like an excellently-formatted patch from someone …. and I have no idea why I would want to incorporate this feature or support this code for eternity. If I have no idea what feature you are adding, or what problem this solves, your pull request will get closed at this point. The trick here is to spell out to me why this is awesome and I should immediately get this code into the project.

Does It Relate To A Ticket (And Only One Ticket)?

I assume your project uses some way of keeping track of tasks, issues, bugs, however you name them. Find out if there is already one of those things for the change you want to make, and reference it in the pull request. I wouldn’t reject a change without a ticket number (some teams will), or simply because it covered more than one ticket, but it’s more likely. A change covering more than one ticket that really aren’t closely related will probably get closed at this point. A couple of related tickets, or a great idea that didn’t have a ticket …. those I can entirely engage with.

Do These Changes Touch The Tree As You’d Expect?

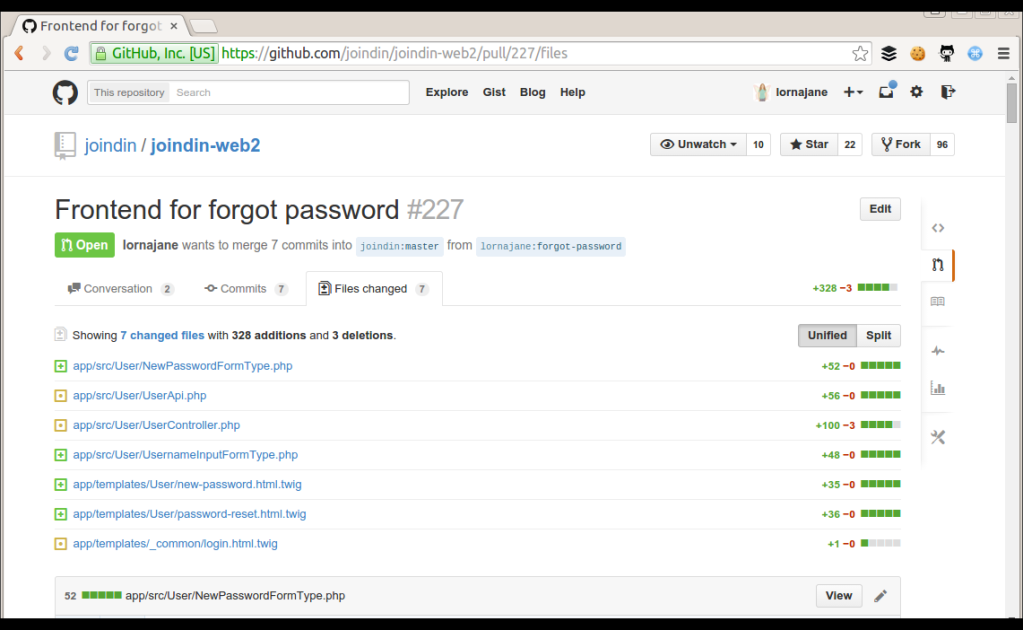

If you think you’re getting a new database column and there’s a change to the CSS file, that should be obvious just from looking at the list of changed files. I like `git log –stat` for this but the web interfaces such as github will offer a summary view of a diff (click on the “N changed files” link) as well which is the same thing. Look out also for surprisingly high numbers of changed lines – last week I spotted that we had accidentally committed a minified version of something for example, and you don’t need to get as far as the diff before that sort of thing is obvious.

If you see unexpected changes, or changes not where you would expect them (this second one requires a lot more experience), then ask questions. I like to be patient but especially at work, if I see a mispackaged change which includes too much stuff or is clearly missing a file, I just reassign it back to the developer to get them to update it.

(The changes you expect should also include database patch scripts, test, documentation, etc. Those are the files that can be hard to spot if they’re not there!)

Does The Commit History Make Sense?

As a person who has been known to tell colleagues “That is not a commit message. Try again”, I’m quite fussy about this. The reason is purely that I know how much I have hated my past self for rubbish commit messages in the past!! A good commit message follows on from a good commit, so if you are having trouble writing a short and coherent message, then consider stopping, resetting your staged changes, and adding in smaller units to make a larger number of self-contained commits. There’s a great article on writing commit messages that I think can really help: http://chris.beams.io/posts/git-commit/.

Other commit message weirdness to look out for here includes seeing commits that don’t belong in this branch. Whether you choose to unpick and recreate the change or not is up to you but pull requests that include a lot of other commits from another change (which might have been rejected) because the contributor branched from the wrong place have eaten many hours of my spare time! I usually think it is worth trying to correctly package all changes; as a developer you can check that it’s going to look OK by scrolling down the page when you create the pull request – it will show you the commits that will be included and the diff, so if you’re branching or requesting a merge to the wrong places, usually you can tell this is the case!

Eyeball The Diff

Before I really get into detail with the code, I do cast an eye over the diff and look for anything really strange. These would include:

- Large sections of commented-out code

- Copy/pasted code

- Silly variable or function naming

- Any syntax so exotic that I have to ask what it does …. always ask! Either you’re picking up an important potential issue, or you’re about to learn something. Both are great outcomes :)

Whether I will close a pull request with these mistakes in really depends on the context. If I have to work with this person again, then I will comment and request the changes I want to see to make it right. If it’s an open source contribution and I think it’s unlikely to be amended or if I urgently want to ship the change, then I will sometimes fix some things myself. It’s very common to see a merge request come in from me that it someone else’s branch plus one more commit from me fixing something tiny … totally worth getting the spelling right in the comments, or maybe the route name the developer chose didn’t fit our overall scheme – if I do this, I;ll mention it in the discussion on the pull request. If it’s small, I always consider this option – but since I don’t want to be cleaning up after the same people making the same mistakes for the rest of my life, I make actual colleagues fix things themslves!

Now Run The Code

It might seem strange to have done so much with a pull request without even seeing if it works, but I think all of the above are important for the health of the project. If a change isn’t correctly packaged, can’t be run on other platforms easily, or decreases the quality of the existing codebase, then you don’t want it. By making these inspections up front (especially that first one: What is this actually *for*?) will very often save a lot of time later on, but as developers we love code and the temptation is to jump straight in. I expect all members of a team to take on code review, and for them to take it seriously. When I do see a bug in a newly-merged branch, I ask first who reviewed it, not who built it. Hopefully some of the ideas I’ve shared here from my own practice will help you in your work, too! If you have other tips to share, I’d love to hear about them in a comment.

Pingback: PHP Annotated Monthly – June 2015 | JetBrains PhpStorm Blog

Pingback: The beginner's guide to contributing to a GitHub project | Rob Allen's DevNotes

Pingback: Como contribuir com um projeto no GitHub -

Pingback: The beginner’s guide to contributing to a GitHub project – Rob Allen's DevNotes